GO COLLECTIVE OR GO HOME!

tracing the neo-avant-garde mindset in contemporary architectural practices

: katarina petrović w/

michele rinaldi

| y 2019

The term “avant-garde” in architecture has been often used as a synonym for “extravagance” or “up-to-dateness”, dismissing the complexity of the term and reducing it to the level of cliché. This is not a coincidence. There are no clear criteria defining the avant-garde in architecture, making its use extremely complex and ambiguous. The common thread weaved into the many definitions that historians and critics have given to the avant-garde in architecture is the sense of its renewing power in the social and ideological core of the discipline and profession:

Avant-Garde's first task is to change the nature, the boundaries, the dynamics, the evaluations and the internal rules of architecture. In other words, its first task is to redefine or alter architecture's cognitive, evaluative and normative grounds. ¹

The redefinition of these grounds can be traced historically. What can history teach us about the avant-garde mindset in architecture? Are there any practices today still redefining or altering these grounds, and why is this relevant?

In 2008, the well established architectural figure Patrik Schumacher, principle at Zaha Hadid Architects, presented Parametricism as Style - Parametricist Manifesto² at the Venice Biennale. In the same year he published Parametricism - A New Global Style for Architecture and Urban Design³ where he argued that:

There is a global convergence in recent avant-garde architecture that justifies the enunciation of a new style: Parametricism … This style has been developed over the last 15 years and is now claiming hegemony within avant-garde architecture.⁴

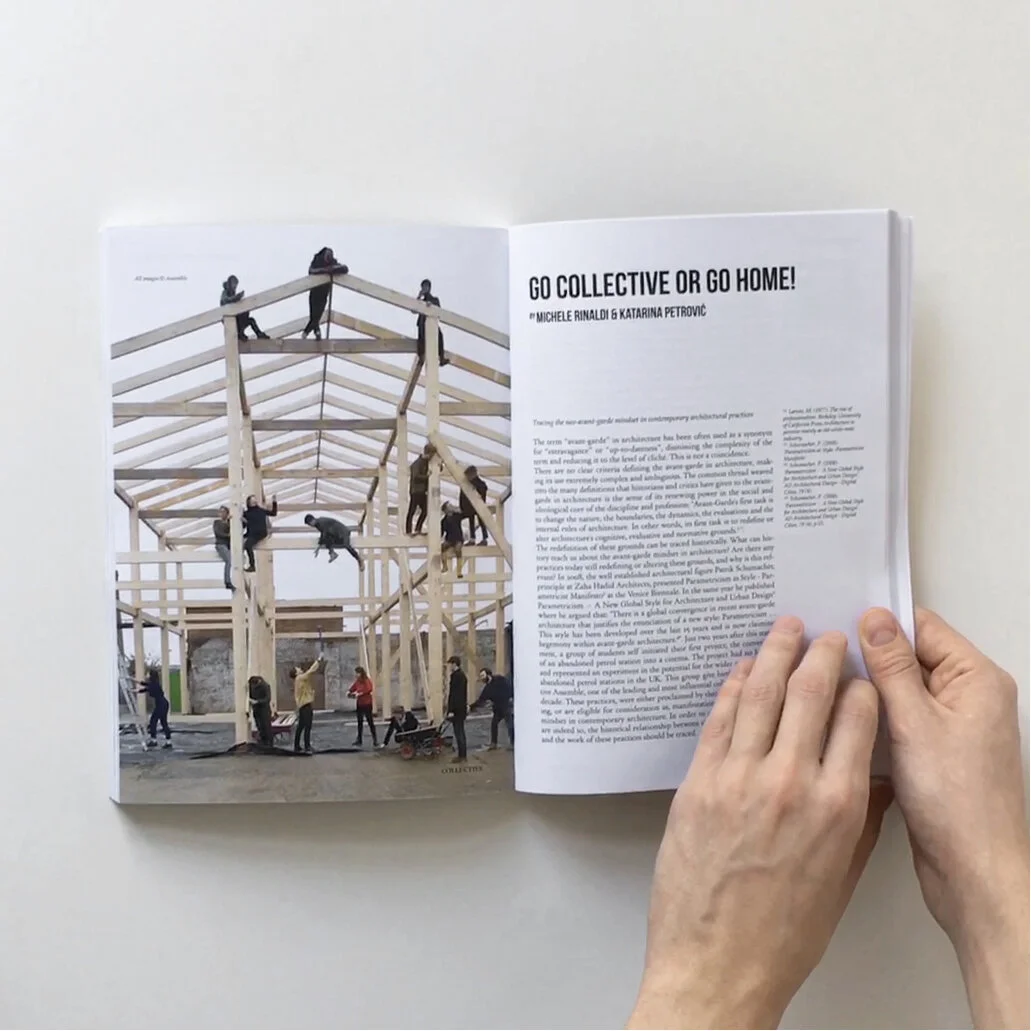

Just two years after this statement, a group of students self initiated their first project; the conversion of an abandoned petrol station into a cinema. The project had no budget and represented an experiment in the potential for the wider reuse of 4000 abandoned petrol stations in the UK. This group gave birth to the collective Assemble, one of the leading and most influential collectives of the last decade.

These practices, were either proclaimed by their proponents as being, or are eligible for consideration as, manifestations of the avant-garde mindset in contemporary architecture. In order to consider whether they are indeed so, the historical relationship between the previous avant-garde and the work of these practices should be traced.

AVANT-GARDE AND EXTERNAL CONDITIONS

Since architecture is by default intertwined with external conditions, such as the ruling establishment system and the distribution of power, one of the key points in tracing the avant-garde mindset is its relationship towards these conditions. All of the past avant-gardes were anti-establishment, and the desire for a systematic reconstruction of society was in the very essence of their radicality. In 1961, during the era of crisis and crumbling late modernism in the UK, the neo-avant-garde protagonists Archigram released their Manifesto where they state that:

A new generation of architecture must arise—with forms and spaces that seem to reject the precepts of “Modern”⁵

In this statement, “Archigram would perpetuate the revolution by taking a collective stand against those who wanted to make modernism into a methodology”⁶. For the neo-avant-garde, the main goal was to escape the totalitarianism and uniformity of the way that architecture was practiced and executed. The “Modern” was at the time the symbol of the well-established system that was deeply entrenched, and which became mannered and stopped being beneficial to the ones that were not in power.

Archigram’s work was part of a larger shift in avant-garde concern in the 1950s and 1960s, from the creation of singular “works of art” such as paintings and buildings to the exploration of art as a lived medium, as a way of structuring everyday life for all.⁷

By raising the question “For whom?”, the neo-avant-garde, with a Robin Hood mindset, stood up as defender of the majority. For instance, avant-garde in the 1960s became concerned with the fact “that many Europeans acquired fully plumbed, indoor lavatories for the first time”⁸. Archigram and other such collectives were aimed at creating new societies, focused on bringing benefit to all; to do this, the systems that had not been in the interests of everyone had to be revised and reconstructed from the core.

50 years later, again facing an era of economic and housing crisis, Schumacher states that “a decisive shift towards an unencumbered free market system would indeed be revolutionary”⁹. At first glance, this statement mirrors the radicality of the avant-garde mindset in terms of its systematic rethinking of society. But where his theories part ways with the previous avant-garde is the answer to the question- in whose favour is this systematic reconfiguration? If we were to pragmatically analyse the clients for whom Schumacher builds, we would find a long list of high-end corporate giants and institutions; in other words, the corporate interests holding the cards. An ideology which supports a rampant free-market, which in reality works just for those in power, is dangerous, because it results in a society aimed at fulfilling their needs, and it creates an even larger polarity in society between the haves and have-nots that deepens the original crisis. Schumacher’s loud claim to the avant-garde reaches the dangerous domain of cliché, because it is the intentional one. Its superficial radicalism conceals a darker motive; it hijacks the appealing connotation of avant-garde for nothing more than a tool to abolish competitors in a race to construct visually pleasing buildings for corporate interests. It ignores a key historical element of the past avant-garde - bringing value to those who are not in power.

On the other hand, collectives such as Assemble do not make eye-catching ArchDaily headline-grabbing statements. They are instead interested in a proving-by-doing type of radicalism. Assemble imagines and creates alternative ways in which the systematic network at the base of their projects can be reconstructed. Assemble defines this experiment as an “open process” in which they, for each project, tailor, customise and negotiate the unique systematic setup with the institutions and future users of the space. They initiate their projects, establish independent organisations and focus on the uniqueness of each process rather than following the “Modern” established procedures. For example, Assemble’s practical solution to the housing crisis is seen in their Granby project “that in its very core idea abolishes the idea of the masterplan” ¹⁰. By initiating a collective local ownership negotiated with institutions as a base for the execution of a series of small interventions by locals, Assemble managed to reverse the fortunes of one of Liverpool’s rapidly declining neighborhoods on all levels - social, economic, political and thus architectural. The whole process did not just include the typical “participation on paper” type of community inclusion; instead, it was a real, in situ one, where the community members collectively rebuilt their houses, as well as designed and built furniture in their community workshop. By piloting new prototype systems of development, such collectives are leading by example in demonstrating how architecture can essentially reject the precepts of the “Modern” ¹¹. On the other hand, Assemble’s deep concern with the basic needs of have-nots, and generating value for those that are not in power, progresses the core avant-garde mindset.

EDUCATIONAL AND ANTI-ESTABLISHMENT

The architectural establishment is also largely represented by academia, which officially plays a role in training new generations of architects and participating in public discourse. The most influential architecture schools are avid collectors of well-known architects in their teaching staff in order to keep a status of public recognition and credibility. The avant-garde has historically presented its ideas through independent magazines, exhibitions and debate as a counterpart to academia. Despite that, the avant-garde does not reject architecture schools per se; but rather it fights the academicism of such schools. The key role of education in the avant-garde is represented by the “cultivation of individuals working in concert, uninstitutionalised”¹² to train a new generation of architects aware of the role of the establishment and of critical thinking. If we come back to the 1960s, Archigram “also gained an avant-garde, “revolutionary” kudos by consistently targeting youth (in the schools of architecture) as potential agents for change, portraying architecture as being in the throes of a generational struggle”. ¹³

If we think to the research project “Corporate Fields”, supervised by Patrick Schumacher at the Architectural Association, it is clear how academia and the people that hover around it could spread ideas supporting the embedment of the establishment within architecture. Architectural students were encouraged to collaborate with “ (...) corporate quasi-clients: BDP, DEGW, M&C Saatchi, Arup, Microsoft UK or Razorfish … creative leaders in their own fields. (...) On a more general level these scenarios respond to the innovative work patterns of a ‘post-industrial’ economy”. ¹⁴

In opposition to institutionalised schools are the “fictional” schools as shown by the examples of the open raumlabor university (“ORU”) and the Floating University, both developed by the Berlin based collective raumlabor. The ORU is for example “part of a wider move to shift from project to practice and essentially seeks to open up a common space for exploration, improvisation and collective experimentation. It focuses on the curiosity and sense of wonder practices together. The open raumlabor university is not fixed in time and space, and its structure and methods will vary with the context of each occurence. The ORU seeks to create a learning environment based on dialogue, deep collaboration and lasting relations”. ¹⁵ Those examples represent the determination of the collective to find their space outside academia in order to raise awareness and criticism through experimental forms of learning of participants, who will be encouraged to exchange experiences and develop and teaching based on a “on camp” educational system divorced from any corporate intrusion.

NON STYLE

In their manifesto, Archigram is openly rejecting curtains, the curtain walls symbol of the modernist homogeneity and design:

(...) design (as in the cut-and-dried presentation of a solution) was too static, premeditated and removed from environmental context to be literally transcribed into built form; there could therefore be no more design in the traditional sense of the word.¹⁶

When Schumacher defines Parametricism as a “style of avant-garde practice”¹⁷ and refers to it in terms of “mainstream hegemony” ¹⁸, he is bringing the meaningfulness of the avant-garde to a dimension of homogeneity and mannerism that avant-garde has always tried to avoid. The hegemonic style he refers to serves, in reality, as a tool for his personal recognition:

Parametricism is therefore posed to aim for hegemony and combats all other styles.¹⁹

This combat or "style war" is fought on the battlefield of formal research, eluding any other category of discussion. Indeed, the endless generation of facades and masterplans by the latest computational design technologies is not far removed from the “curtains” of Archigram’s Manifesto. The whole design process is delegated to computational technologies, and the resulting designs ignore the complexity of their context and surroundings. As Schumacher states:

Today it is impossible to compete within the contemporary avant-garde scene without mastering these techniques.²⁰

This codification of the avant-garde as a style puts the focus on its output, the built form, prioritising its formal potential over the experimental and innovative systematic process behind it, which has always characterised the avant-garde throughout history. Looking at architecture just as a built form is reductive, and thus inefficient. What the avant-garde emphasises is not exclusively the codification of the design itself, but also the systems that are seeking to influence it.

When, for example, we observe Assemble’s work, the design phase is not limited to the physical and material appearance; it is exploring its organisational power and expanding the range of activities it can provide for and create. This performative modus operandi puts the focus more on the process that actually leads to the definition of spatial qualities of a specific project rather than its final appearance as a built object:

It's more about understanding of what shared process is, and the process of making or understanding projects is shared - whether the work is architecture or art becomes not so interesting. ²¹

Users are invited to play a protagonist role in the modification of space, as shown in the Baltic Street Adventure Playground, the design of which was developed directly on site with an intuitive construction process undertaken by users able to bring everyone closer to the design phase. This approach explores the potential of design through a process that manages and considers the impact of a project in a certain context, the user's experience and a project’s sustainability. This is far from Schumacher’s highly conceptual and top-down vision based on the questionability of style. If one considers Assemble, and in general the works of other collectives, it will come as no surprise that no particular stylistic desire can be deduced. One can easily recognise how, in their modus operandi, they do not use design just as a tool for being recognisable or appealing on the market.

AVANT-GARDE AND INTERNAL CONDITIONS

ANTI HEROISM

The image of a mastermind architect standing behind a model of their building - claiming authority over and credit for it - was a dominant way of representing architectural personae throughout the 20th century, which culminated with the “modern heroism”. With the rise of the media, modern architects such as Le Corbusier or Mies van der Rohe were popularised worldwide as icons of their time.

Neo-avant-garde found this idea of architectural personae too totalitarian. Collectives such as Archigram, Archizoom and Superstudio valued collaboration and architectural anonymity as the central drivers towards restructuralisation of society. Instead of heroism, these collectives were organised together into non-hierarchical, flat structures that themselves represented collaborative, egalitarian and democratic bodies. Their very organisational formation mirrored the processes behind their own architecture, and served as a prototype of their desired societal structures. The desire for anonymity was for them more than an ego issue - it was a statement against totalitarianism and ‘cult of personality’, a fight against hierarchical distribution in society.

If one analyses today’s architectural milieu, one can draw a parallel with the modern heroism, wrapped up in the term “starchitect”. Starchitects are given large media coverage, find acclamation within the mainstream culture, and through their personal brand generate exposure for their brand of architecture. The firm of 400 employees led by Schumacher, which he would refer to as the “high-profile creative firm” ²², in terms of internal structure has no difference to any corporate architecture firm. This means a strict hierarchical top-down structure of directors, associate directors, senior associates, associates. If we take as a guiding principle that the internal organisation of a firm or group manifests and reflects the desired structure of society, how can this type of highly uniform and hierarchical structure progress the avant-garde mindset?

Speaking of their own internal structure, Assemble has claimed that the development of that structure and their work methods has been their biggest project. And that it “has always been an organic project itself, not something that was planned from the start, but something which develops naturally”. ²³ What is a non-changeable base is the organisation of the multidisciplinary collective in a flat structure. Assemble refers to its organisation as “a platform for people to develop their own interests with the support of the group. Whilst it shows as a good model, it survives, when it doesn't function anymore, we change it”. ²⁴This internal organisation reflects the society that is open to change according to needs or circumstances.

AVANT-GARDE AS A TRIGGER TO A PROGRESSIVE SOCIETY

The criteria analysed above all carry the leitmotif of previous avant-garde without constituting a stagnant, unchanging checklist. Rather, they provide operative points of reference to be taken up and incorporated into contemporary practice. Looking to past experience is still relevant to today’s conditions, because the avant-garde is, in its essence, a collective social change mindset, a way of progressing through critical thinking. In this way, it is universal and timeless. This awareness helps us to detect possible manipulative intentions behind the mystification of the term avant-garde as seen in Schumacher’s theory. This type of attitude is directed to schooling society to accept its hegemonic precepts; even where those precepts are not beneficial for everyone. Indeed, they may be detrimental. Assemble and other such collectives are redefining or altering architecture's cognitive, evaluative and normative grounds and reconstructing the role we all play in society. It is irrelevant to discuss the existence of the avant-garde as a movement today. The relevance of the avant-garde is demonstrated by the continuous mindset that collectives such as Assemble hold. These protagonists are triggering the social change of today's society. But for such change to actually happen, we should all collectively take a stand with these practices and the avant-garde mindset, actively redirect our society further as the avant-garde essentially aims.

Go collective or go home!

▲ Cover of the STUDIO #17, authors Bangkok domestic tastes. A. Lazzaroni & A. Bernacchi (Animali Domestici), INDA

An interaction with Michele Rinaldi

Michele is a Berlin based Italian architect. He believes that architecture is a multidisciplinary dialogue in which the imaginative powers of photography and visual arts play an important role in the act of transforming and defining spaces. He likes to portray unspectacular walls and neglected facades.

References:

1- Larson, M. (1977). The rise of professionalism. Berkeley: University of California Press.

2- Schumacher, P. (2008). ‘Parametricism as Style - Parametricist Manifesto’. Retrieved from- Link

3-Schumacher, P. (2008). ‘Parametricism - A New Global Style for Architecture and Urban Design’, AD Architectural Design - Digital Cities, 79 (4).

4-Schumacher, P. (2008). ‘Parametricism - A New Global Style for Architecture and Urban Design’, AD Architectural Design - Digital Cities, 79 (4), p.15.

5-Archigram Magazine Issue No. 1. (1961) Retrieved from -LInk

6,7,8- Sadler, S. (2005). Archigram: Architecture Without Architecture. Cambridge, Mass., MIT Press.

9-Schumacher, P. (2018). ‘Only Capitalism Can Solve The Housing Crisis’, Adam Smith Institute. Retrieved from- LInk

10-Canadian Centre for Architecture channel (2016) Assemble: Collective Practice. Retrieved from - Link

11-Archigram Magazine Issue No. 1. (1961) Retrieved from - Link

12,13- Sadler, S. (2005). Archigram: Architecture Without Architecture. Cambridge, Mass., MIT Press.

14-Schumacher, P. (2005) ‘Research Agenda’, in Corporate fields. Edited by Brett Steele. London: Architectural Association.

15-Open raumlabor University. Retrieved from - Link

16-Sadler, S. (2005). Archigram: Architecture Without Architecture. Cambridge, Mass., MIT Press.

17-Schumacher, P. (2008). ‘Parametricism - A New Global Style for Architecture and Urban Design’, AD Architectural Design - Digital Cities, 79 (4), p.14.

18,19- Schumacher, P. (2010). ‘The Parametricist Epoch: Let the Style Wars Begin’. Retrieved from - Link

20-Schumacher, P. (2010). ‘Parametric Diagrammes’. Retrieved from - Link

21-Canadian Centre for Architecture channel (2016) Assemble: Collective Practice. Retrieved from - Link

22- Schumacher, P. (2019). Interviewed by Marcus Fairs for Dezeen, 29 March. Retrieved from - Link

23,24- Canadian Centre for Architecture channel (2016) Assemble: Collective Practice. Retrieved from - Link