on future romani housing

architectural + social coalition

: nevena balalić w/

milena grbić

| y 2020

Roma settlements have represented part of Belgrade’s urban tissue for decades. The living conditions in these settlements came to be as consequences of a never-ending cycle of poverty in which general deprivation leads to bad education and thus a low possibility of getting employed which further leads to harder access to the social protection and health systems, which again ends in poverty and a low social status. Settlements inhabited by the Roma population are characterized with a legally unresolved status, insufficient infrastructure, overpopulated, general poverty and no access to basic social content and services.

1. Methodology: Logos vs. Nomos

The concept of this work is based on considering the present confrontation of two opposing spatial ‘strategies’, the Logos and the Nomos, which are present when conceiving activities for unplanned settlements in the field of redevelopment as land management, planning, and new construction or reuse on previously used sites. One strategy, the Logos, develops theoretically or institutionally as an abstract space of professionals (e.g. architects, urban designers, planners), and the other – the Nomos, represents a concrete space of the users, which is subjective and develops spontaneously. Terminologically, the denotative determinants of these two spaces are based on the structuration of space according to Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari. The Logos represents a ‘called for’ conception of existence and offers an image of space that is primordially created in various ways, which simultaneously limits it. This space is considered ‘furrowed’. On the other hand, the Nomos indicates that the space has no institutionally imposed organization and thus needs to be understood as open or, as Deleuze and Guattari call it, smooth space¹. Henri Lefebvre methodologically indicates that investigating any (urban) phenomenon, therefore including those related to illegal settlements, needs to start with formal characteristics of space, and only later refocus on investigating the discrepancies within spaces and contents because every urban phenomenon methodologically already depends on familiar notions – dimensions and levels², with clear awareness of the fact that urban phenomena contain not one but several systems of signs and meanings, on several levels.

2. Nomos: Screen of the Mundane in Informal Roma Settlements

In the context of institutional space, informal settlements are understood and analyzed as a set of ‘primitive huts’ in places they were not planned. However, except for the necessary concretisation of existential space, their meaning can be deepened when enclosed spaces are perceived as constructed places. In terms of phenomenology, informal settlements, especially Roma settlements, represents ‘an inside inside an outside’, meaning a space inside a space, but not just in terms of a housing unit created through enclosing and separating a segment of space, but also in terms of symbolical representation of the builder (encloser) in social space. There are no design pretensions of institutional space in informal Roma settlements, and the organic connection between man and unbuilt environment is practically claimed through reflex. That means that the formed living space of the informal settlement didn’t withstand the influences of l’habitat in its organization - l’habitat, which, to use Lefebvre’s understanding, reduces housing to its basic elements and neglects the relation of the ‘human being’ to the world, the ‘nature' and its own nature³. Given the context, it, as a physical space formed by its inhabitants, represents a smooth space, in contrast with the sharpness of the city environment, which is to say it represents a spatial quality that came to be through reflex, according to the needs of everyday life. Observing the Roma settlement as a place opens the possibility of accepting such spatial organization that includes the basic elements of family life, lifestyle, cultural models and other values in relation to everyday life. When the phenomenon of informal settlements is understood in that manner, further research is conceived so that it uses analysis to try to showcase the fact that these settlements contain the general philosophical problem of the man-space relation which can be explained using the basic principle of the methodological creation of architecture.

In that sense, a formulation of several conceptions of physical structure was noticed in informal Roma settlements in Belgrade and Serbia, studied by the authors of this work since 2006. Through a series of circumstances, these physical structures integrated, at different scales, spontaneously achieved principles of spatial formation, and thus the potentials for further acceptable improvements in the area of resolving the housing issues of the socially endangered Romani.

FAMILY

The collective lifestyle in Romani in Belgrade is dominantly noticeable on the family organization level. A primary Romani family counts five members and is made of a husband, wife and three underage children. As field research has shown, when the children grow up and start forming their own families, they rarely separate and leave their birth home, but stay within proximate frames of the same household thus creating an expanded family. This three-generational structure that the Romanis call – endaj, is the most frequent household organization in Romani settlements in Belgrade. A typical Romani expanded family, is then comprised of a husband, wife, their sons and daughters-in-law and their children.

The fact that expanding the family does not always implies moving or building a new house and creating a new household but it primary points to the transformation and expansion of the parental house, the first question is open about what kind of structural omnibus makes an entity that can be named a Romani home.

COMMUNITY

The term family in the Romani culture is still expanding and it matches the term community where the individual is less important than a group. The individual ambition and desire for social rise and reputation is generally not developed with the Romani, but a collective way of life on the community level is preferred as a synonym for protection, security, surveillance, guidance and previously established rules so it wins its place over the individual lifestyle which is considered to consequently lead to uncertainty and lack of protection and freedom.

HOUSE

Main characteristics. A characteristic Roma house is a house built using non-standard construction materials, most frequently waste materials. Slum inhabitants call their houses ‘barracks’ whereas the term ‘kartonka’ (lit. cardboard house) is used in colloquial, everyday communication, as to refer to housing built from cardboard and other non-construction materials (thus came the slang nickname for slums – ‘karton siti’ (lit. cardboard city)). Even though it is hard to precisely determine, the usual basic construction of the temporary houses is made out of wooden beams or planks, although there are cases where it’s made out of steel or concrete. The materialization around the base construction is achieved with coating using wood boards, doors, waste nylon foil, waste sheet iron or cardboard. Roofs are shed or gable roofs, with low slopes. The roof cover is placed on wood boards in the direction of the roof slope. Waste nylon foil, cardboard, sheet iron, cane as well as waste asbestos plates (formerly used for covering, now discharged because of the effect asbestos has on health). Floor is bare ground with cardboard or Styrofoam covering. After forming the outer layer, the house is equipped from the inside by linen and textile coverings, making the whole interior look like patchwork. The temporary house therefore represents – a secondary architecture – a house from waste resources which is never larger than 15 square meters due to its structural capabilities and materialization, and is always up to 1.8 meters tall. This height also determines the volume of the house, which is usually around 30 cubic meters, and is easier to heat in the winter; the height also makes it easier to fix the roof if necessary. Functionally a basic space is created out of a living room, kitchen with a dining room and eventually a bedroom .

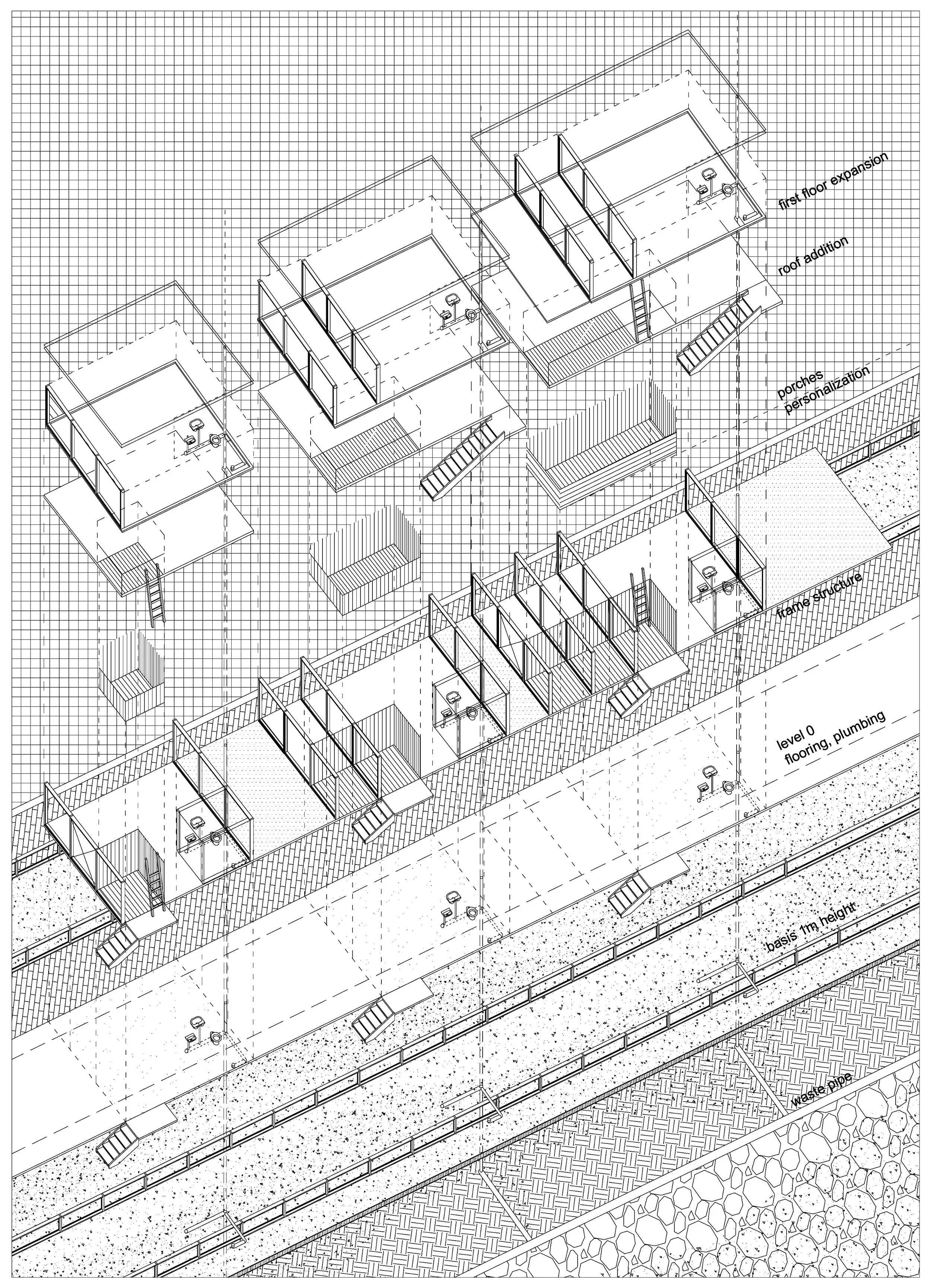

▲ exploded axonometric view of a continuous skeleton

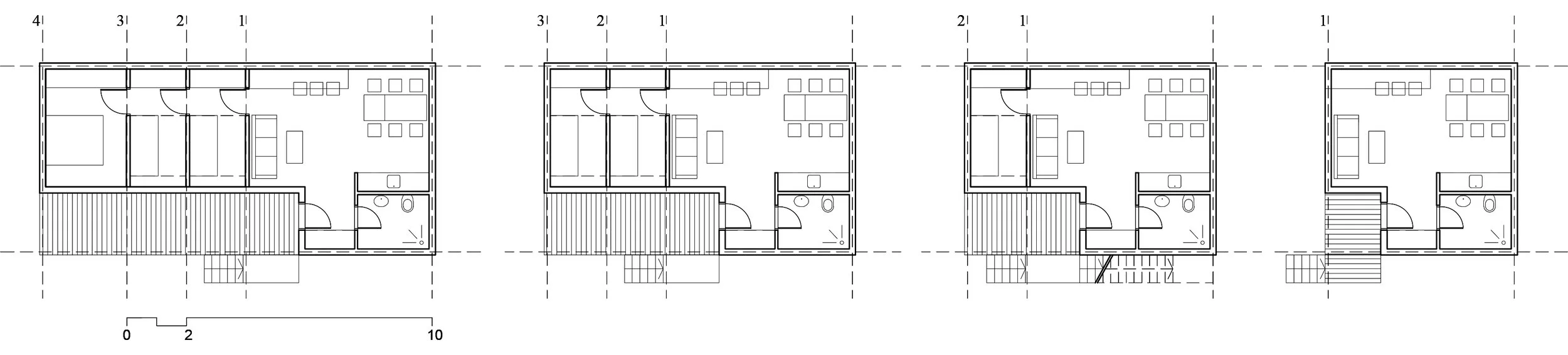

▲ floor plans; expansions of the house

THE HOUSE-BUILDER AND BUILDING A HOUSE

The builder of a temporary house is the most skillful ‘architect’ in the settlement. According to the conversations led by the authors of this work with the inhabitants of the slums, the head ‘barrack’ builder is the one who is “the most adept in basic construction work with wood and iron sheet and who knows how to best combine bus doors, car windows, wooden jambs, waste wood, cardboard, iron sheets and tires”, but “everybody helps him”. The settlement’s architect must work quickly and if the householder turns out to be a good assistant, the house may be built within a day. The neighbouring house in the settlement never abuts the existing one, but an aisle of minimum 1m in width is left between for quick repairs and alterations, i.e. sanation. The inhabitants themselves execute the replacement of elements on the roof, walls, and floor. Besides the sanation, the annexes and adaptations may be done as well after the construction of the house.

The field research has shown that expansions of the house, i.e. annexes and adaptations, are a permanent on-going necessity for the residents, generated as a response to the adaptability to the transformation of the family structure. The construction of the barrack happens in stages and it grows along with the expansion of the family. Because of the initial lack of space, many rooms of the temporary house are constructed subsequently. The annex is most frequently a room of about 10 square meters in area. The annex and the adaptation of a temporary house are done by residents themselves with possible help from relatives and neighbours.

With regards to self-build and self-help, it is important to shortly summarize that the house actually represents a unique product that takes around 24 hours to build as the architect can always count on the help of the homeowner and the other inhabitants. Family participates in all of the phases of the construction of temporary houses and annexes and that the most frequent element to be annexed is a room. In other, more complex procedures, the community is also involved.

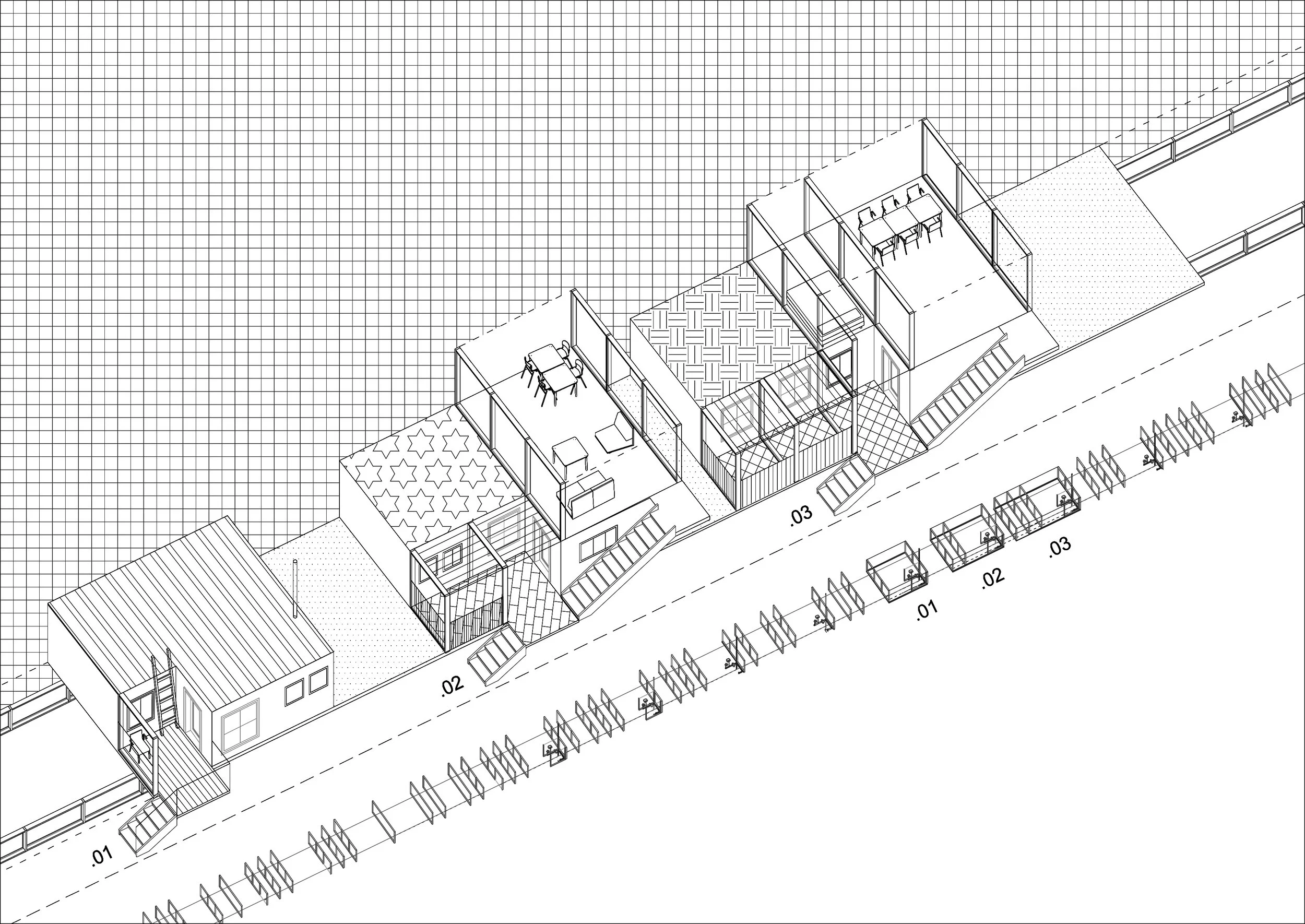

THE PORCH

The porch serves as a space to prepare food and have meals. Its position is determined by the cultural dimension of activities that take place. The porch is visually explicit. This sort of gesture is deeply rooted into the Romani cultural tradition and their relation to food. As Acton and Mundy instigate, not having food for a guest is a very shameful gesture and the family would be marked as the one that saves up on food.⁴

The ascertainment that food is not only an item of biological survival but also a ‘social phenomenon’ brings into immediate connection habits in nutrition with producing this spatial content. Based on field research, the existence of a summer kitchen and dining table was noticed, found on the porch in all types of settlements and all types of houses. One of the conclusions of this study is that the cultural distinction concerning food initiated the existence of this space which enables a visual exposition of the food preparation and consummation process as acts of passing on ‘something’ (one of the ways of presenting wealth) to their surroundings. It contributes to imagining the approach to higher classes despite the fact that they are, objectively, based on real economical possibilities, closer to lower classes of society. In that key, the porch that has primarily a private use is positioned on a visible place and collaterally towards the street visually opening toward the community.

3. Design action: Logos feat. Nomos

Our concept of Roma housing is based on a continuous skeleton formed both by Logos and by Nomos.

The skeleton dimensionally belongs to Logos because it is formed according to numerical values that allow the volume of healthy living space in every sense. The continuous skeleton also ensures the continuity of preserving family values and community values.

The program and the shell belong to Nomos. The content of the program and the way it is grouped are the result of research and insight into the importance of their existence, which are deeply rooted in Roma culture.

The shell allows the personalization of the home. This is of double importance. On one hand, it respects every lifestyle, and on the other, it involves the resource of a resident's ability to self-construction.

An interaction with Milena Grbić

Milena Grbić Ph.D. Arch. works as an assistant professor at the University of Novi Sad. Lives in Belgrade, Serbia.

References:

1- Parr A. (ed.) (2005), The Deleuze dictionary, Edinburgh University Press Ltd, Edinburgh.

2- Lefebvre H. (2003), The Urban Revolution, University Of Minnesota Press, Minnesota.

3- Lefebvre, H. (1991(1974)), The Production of Space, Blackwell Publishing, Oxford, UK.

4- Acton T. and Mundy G. (1997), Romani Culture and Gypsy Identity, University of Hertfordshire Press, Hatfield, GB.